| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

report so the limits to growth report as it was released they did an update in 2008 where they looked at it where they projected the data from 1970 to the year 2000 on the standard run and the data projected onto that fits roughly the same pattern that shows conceptually the limits of growth report was conceptually correct what they got it badly wrong was when you know uh it's it's a trend that goes across a century so so at what point do we hit a problem i don't think anyone knows that so all i've done here is if we think we are going to replace the system as it is now now now how much metal will we need to manufacture the needed number of units to do that so the obvious outcome is we won't do it we will have less technology units we'll we'll have to shrink the system somehow and so the future will not look like anything like what i presented because we've been moving in a particular direction with our industrial ecosystem.

スティーブン・ヘイル「解説:MMT(現代金融理論)とは何か」(2017年1月31日)

オーストラリア・アデレード大学経済学部講師

スティーブン・ヘイル

政府支出削減を求めるという困難な選択をするときに、俗に言う『予算ブラックホール』について心配しない経済学の学派がある。バーニー・サンダーズ氏のチーフ経済アドバイザーであったステファニー・ケルトン教授のようなMMT(現代金融理論、現代貨幣理論。以下、MMT)提唱者は、オーストラリア政府は予算を均衡する必要はなく、経済を安定させる必要があると主張する。そして、彼らの主張は(今までの経済学のものとは)まったく違うものだと言う。

MMTとは、1990年代にオーストラリアのビル・ミッチェル教授(和訳)とともに米国アカデミアのランドル・レイ教授、ステファニー・ケルトン教授および投資銀行家でファンドマネージャであるウォーレン・モズラー氏により経済運営の手法として開発され、ハイマン・ミンスキー、ワイン・ゴッドリー、アバ・ラーナーといった先駆的経済学者のアイディアをもとに築かれた理論だ。著名経済学者ジョン・M・ケインズの研究についてのミンスキーたちの解釈は、 1980年代には支配的になったものとは非常に異なっている。

1980年代までには、ケインズは高失業率の場合のみ財政赤字を許容することを主張する経済学者と見られるようになっていた。ラーナーは、1943年に『機能的財政と連邦政府』という論文の中で、ケインズ主義経済学者は完全雇用を維持するには必要なだけ財政赤字を発生させなければならず、この赤字は普通のこととして受け止められなければならないと述べている。1943年4月にケインズは友人で経済学者でもあるジェイムス・ミードに宛てた手紙で、ラーナーについて、「彼の議論は非の打ち所がない。しかしこれを達成するには天の助けが必要だ」と綴っている。

MMTは独自の解釈と批判を惹きつけている一方で、経済成長を復活させようとする政策担当者の努力を蔑ろにし続けている国際経済環境の中で、力を増しつつある。

MMTには三つのコアの主張がある。初めのふたつは以下のとおりである。

1)自国通貨を持つ国家の政府は、純粋な財政的予算制約に直面することはない。

2)すべての経済および政府は、生産と消費に関する実物的および環境上の限界がある。

一番目の主張は、広く誤解されている主張だ。自国通貨を持つ国の政府とは、自国通貨と中央銀行を有しており、変動為替制度を採用し、大きな外貨債務がないという意味である。オーストラリアはそのひとつであり、英国、米国、日本も該当する。ユーロ圏の国々は自国通貨を持たないので当てはまらない。

2番目の主張は、政府はその気にさえなれば、消費しすぎたり課税しなさすぎたりして、インフレを起こすことが出来るという明白な事実を確認しているにすぎない。現実的な限界を迎えるとき、消費の総合的な水準が、すべての労働力、スキル、物質的な資本、技術および自然資源を投入して生産できる上限を超えているといえる。間違ったものを大量に生産したり、消費したいものを生産するために間違ったプロセスを使用することで、自然のエコシステムを破壊することも出来る。

オーストラリア政府は、通貨発行権を持つ中央政府である。オーストラリアドルが不足することはない。自らそう望み行動しない限りはオーストラリアドルの借用を強制されることもなく、その債務は金融制度の中で有益な役割を担う。

政府は支出のために国民に税を課す必要もない。税金はインフレを制限するためにある。インフレにならないレベルの公的部門と民間部門の総支出を維持するために、課税する必要がある。

これは政府支出と税収がお互いに同額でなければならないという意味ではない。オーストラリアのような国ではそんなことは実際にはほとんど起こらない。そしてこれはMMTの3番目の主張に続く。

3)政府の赤字はその他全員の黒字である。

すべての貸し手には、必ず借り手が存在する。つまり金融制度の中では黒字と赤字は足せばいつもゼロになるということだ。

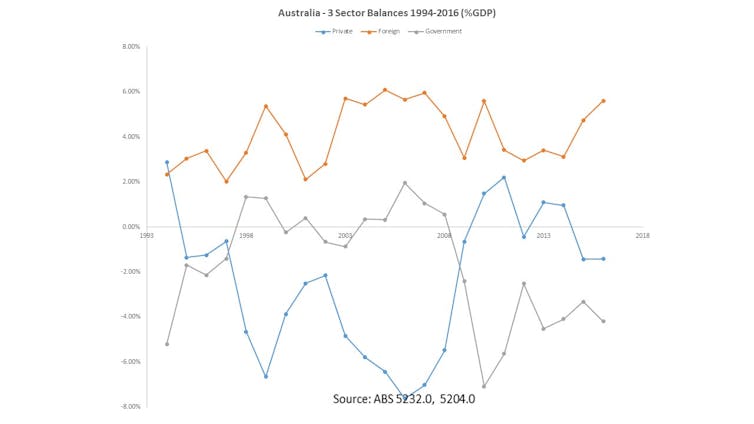

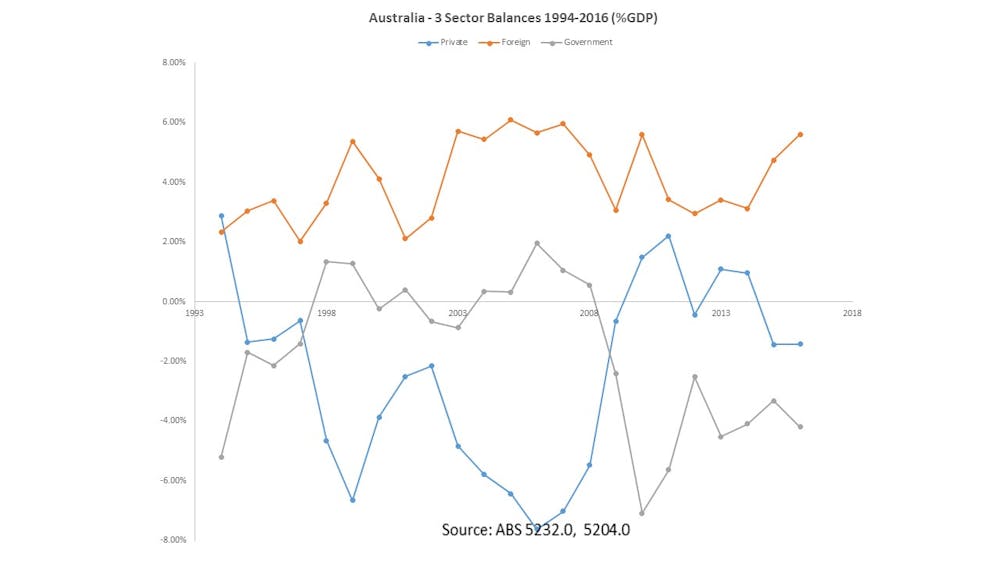

これは下のグラフで明らかだ。1994年以降のオーストラリアの民間部門、政府部門、そして海外の収支バランスを表したものだ。

(図表:1994年-2016年 オーストラリア3部門の収支バランス(%GDP))

消費より収入のほうが多い預金者には、儲けより支出が多い個人か法人か誰かが必ずいる。もし民間部門全体としてもっと借金するよりも貯蓄をしてほしいとすれば、政府はおそらく課税するよりもっと多くを支出しなければならないだろう(他の国の経済がどうであるかによりけりであるが)。

逆もしかりだ。オーストラリアのハワード政府が、財政黒字を出し続けられたのは民間部門の負債額がとても大きかったからだ。

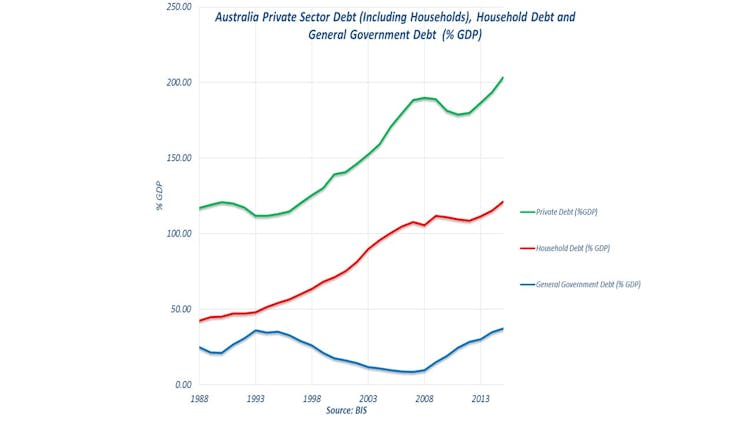

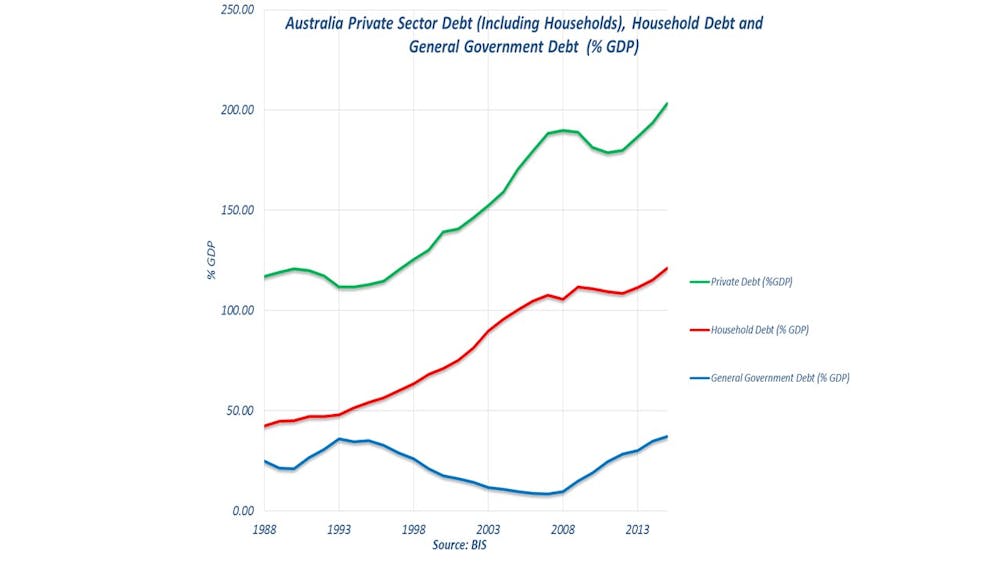

家計負債はハワード政権時代に3倍になった。それ以降、他の2国とともに、対所得家計負債比率で世界最高となっている。

(図表:オーストラリア民間部門(家計負債含む)、家計負債、および一般財政赤字(%GDP))

政府はオーストラリアドル不足になることはないが、だからといって『酔っ払いの水夫』のように浪費していいとか、税金を払わなくていいという意味ではない。予算均衡は必要ないという意味だ。また、民間部門が貯蓄を増やすのを財政赤字は助ける役割も担う。

オーストラリア政府は、ほとんど常に財政赤字を出し続けている。これは何もショックを受けるようなものではない。連邦制になってから平均して右派政権も左派政権もともに財政赤字を出している。(もしあなたがショックをうけたのなら)国家会計を家計に例える比喩に惑わされてしまっている可能性がある。

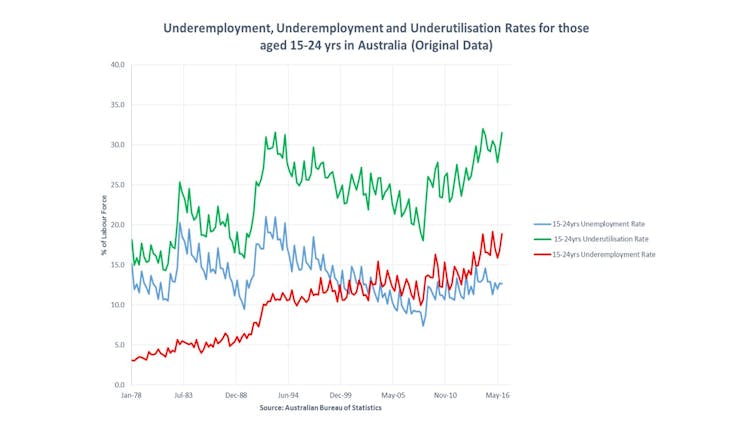

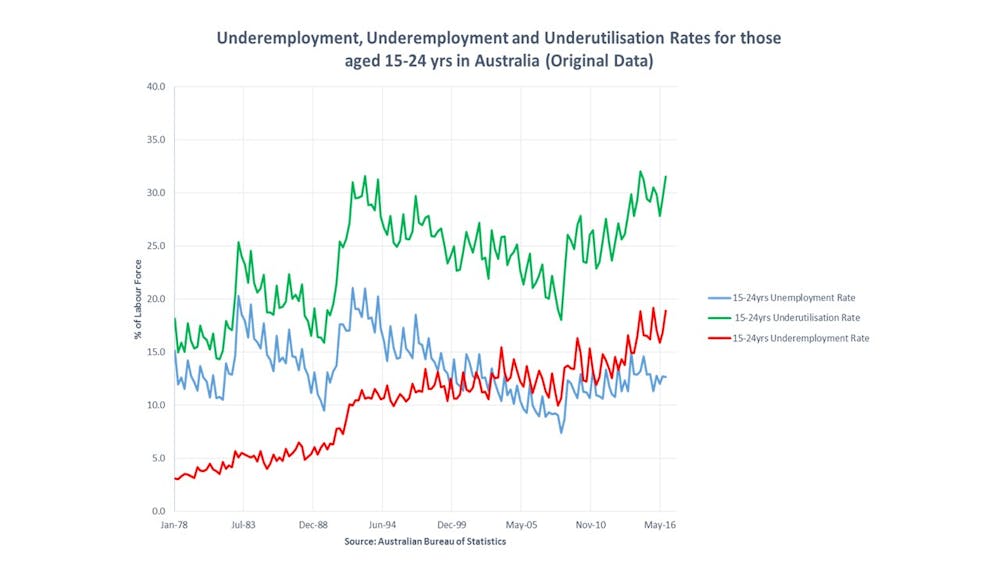

遊休労働力が約15%あり(若年層で30%以上)、民間部門のバランスシートは貧弱で、グリーンインフラおよびその他の(従来型)インフラ投資の必要性の増大している国では、財政再建とはひとびとの注意を逸らすものだ。政府は、完全雇用、ソーシャルインクルージョン、自然環境の回復、健全な民間部門のバランスシートを促進するために、通貨発行機関としての役割を果たすことができるし、そうするべきである。

(図表:オーストラリアの15−24歳における不完全雇用、不完全雇用および遊休労働率(オリジナルデータ))

MMTによれば、政治家は、必要のないこと(予算均衡)にとらわれており、国の未来にとって重要なことの多くを無視している。

これがMMTというレンズを通して見たオーストラリアと世界である。MMTは、現在の金融制度が実際にどのように機能しているかを理解するためのものであり、その点において物議を醸し出すようなものではまったくない。

MMT提唱者であるビル・ミッチェル教授は、政府が自国通貨を持つ主権国としてその政策スペースの中にJGP(ジョブ・ギャランティ・プログラム)を導入し、失業率を2%かそれ以下にすることを訴えている。オーストラリアでこの失業率を達成していたのは1960年代と1970年代の初頭だ。JGPとは連邦政府の資金とローカル(自治体)で運営された公的職業プログラムで、完全雇用への回帰を行うべきとの提案だ。これがインフレを起こすとはミッチェル教授は考えていない。JGPは経済を安定化させインフレを抑制する枠組みとしてMMTに不可欠なものである。

オーストラリアでは、主要3政党はMMTにほとんど注目していない。しかし、米国ではMMT提唱者は政府に近いところに位置しており(上院議員バーニー・サンダース氏とともに)、経済問題を理解するためにMMTの採用を推奨することを目的としたふたつの小さな政党が去年設立された。なので、MMT提唱者と批判者の両方の弁を今後はもっとたくさん耳にすることになるだろう。

- 本稿は著者に特別許可を得て投稿しています。 [↩]

https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-is-modern-monetary-theory-72095

Explainer: what is modern monetary theory?

There is a school of thought among economists who aren’t worried about the so called “budget black hole”, where tough choices have been called for to reduce government spending. Proponents of modern monetary theory, like Bernie Sanders’ chief economic adviser Professor Stephanie Kelton, claim the Australian government need not balance its budget and are instead calling for the government to balance the economy, which they argue is a different thing entirely.

Modern monetary theory is an approach to economic management developed since the 1990s by Professor Bill Mitchell, alongside American academics like Professor Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, and investment bankers and fund managers like Warren Mosler. It builds on the ideas of a previous generation of economists, such as Hyman Minsky, Wynne Godley and Abba Lerner, whose interpretation of the work of the famous economist J.M.Keynes was very different from that which became dominant by the 1980s.

By the 1980s, most people saw Keynes as an advocate of budget deficits only during periods of high unemployment. Lerner, as early as 1943, in a paper entitled Functional Finance and the Federal Debt, had argued that Keynesian economics involved running whatever government deficit was necessary to maintain full employment, and that deficits should be seen as the norm. Keynes, in a letter to fellow economist James Meade written in April 1943, said of Lerner, “His argument is impeccable. But heaven help anyone who tries to put it across”.

While the theory has attracted its own interpretations and criticism it’s also gaining traction in a global economic environment that continues to defy the efforts of policymakers to restore sustained economic growth.

There are three core statements at the heart of modern monetary theory. The first two are:

1) Monetary sovereign governments face no purely financial budget constraints.

2) All economies, and all governments, face real and ecological limits relating to what can be produced and consumed.

The first statement is the one which is widely misunderstood. A monetary sovereign government is one with its own currency and central bank, a floating exchange rate, and no significant foreign currency debt. Australia has a monetary sovereign government. So does the UK, the US and Japan. The Eurozone countries are not monetary sovereigns, as they do not have their own currencies.

The second of these statements confirms the obvious fact that governments can cause inflation, if they choose, by spending too much themselves, or not taxing enough. When this happens, the total level of spending in the economy exceeds what can be produced by all the labour, skills, physical capital, technology and natural resources which are available. We can also destroy our natural ecosystem if produce too many of the wrong things, or use the wrong processes to produce what we want to consume.

The Australian government is a currency-issuing central government. It cannot run out of Australian dollars. It’s never forced to borrow Australian dollars, although it can and does choose to do so, and its debt securities play a useful role in our financial system.

It doesn’t exactly need to tax us to pay for its spending either. Taxes exist to limit inflation. It’s necessary for us to pay taxes to keep total spending – government and private – at a level which will not be inflationary.

This doesn’t mean government spending and taxation have to equal each other, and in countries like Australia this rarely happens in practice. This leads to the third principle of modern monetary theory:

3) The government’s financial deficit is everybody else’s financial surplus.

For every lender, there must be a borrower. That means that across our financial system, surpluses and deficits always add up to zero.

This is clear in the following chart, which shows the financial balances of the Australian private sector, the rest of the world, and the Australian government sector, since 1994.

For every saver who earns more than they spend, there must somebody or some institution which spends more than it takes in. If we want the private sector as a whole to save rather than go further into debt, the government will probably have to spend more than it taxes (depending on what the rest of the world is doing).

It works the other way around too. The Howard government was only able to run fiscal surpluses because the private sector went heavily into deficit.

Household debt trebled during the Howard years. Since then, we have been in a tie with a couple of other countries for the highest household debt to income ratios in the world.

So, the government cannot run out of dollars; that doesn’t mean the government should “spend like a drunken sailor” or that we don’t have to pay taxes; it does mean balanced budgets are unnecessary. It also means government deficits can play a supportive role, allowing the private sector to build up its saving.

Australian governments have nearly always run deficits anyway. None of the above ought to be shocking. On average, governments of both left and right have run deficits, ever since federation. It just might be that you have been misled by that metaphor of the government as a household.

In a country with nearly 15% underutilisation of labour, over 30% youth underutilisation, fragile private balance sheets, and a growing need for green and other infrastructural investments, it does imply that budget repair is a red herring. This means the government could and should be using its role as the currency issuer to promote full employment, social inclusion, ecological repair, and healthy private sector balance sheets.

Politicians are, according to modern monetary theorists, currently obsessed with something which doesn’t matter (balancing their budget), and are ignoring many things which do matter a great deal for the future of the country.

This is the perspective you get when you start to see Australia and the world through the prism of modern monetary theory. It’s based on nothing more than a comprehension of how modern financial systems actually work, and in that sense, perhaps it should not be controversial at all.

Modern monetary theory proponent, Professor Bill Mitchell, advocates for governments to use the policy space provided for them by monetary sovereignty to introduce a job guarantee and pursue a return to unemployment rates of 2% or less. These rates were achieved in Australian across the 1960s and early 1970s. He proposes a return to full employment through a federally funded and locally managed program of public employment. He does not believe that this need be inflationary - indeed the job guarantee is an essential part of the modern monetary theory framework for stabilising the economy and avoiding inflation.

In Australia, the three major political parties have as yet paid little attention to his ideas. But his fellow modern monetary theorists got close to government in the USA (with Senator Bernie Sanders) and two micro-parties have been set up in the last year with the express intention of promoting modern monetary theory as a frame for understanding economic issues. So you can expect to hear a lot more from both the proponents and the critics of modern monetary theory.

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿